Google Do You Do to to the the the the the the the the the Again and Vanleven Line Go When or

| Antonie van Leeuwenhoek | |

|---|---|

A portrait of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) by January Verkolje | |

| Born | (1632-10-24)24 October 1632 Delft, Dutch Republic |

| Died | 26 August 1723(1723-08-26) (aged 90) Delft, Dutch Republic |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Known for | The commencement acknowledged microscopist and microbiologist in history[annotation i] Microscopic discovery of microorganisms (animalcule) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Microscopy Microbiology |

| Influences | Robert Hooke Regnier de Graaf |

| Influenced | History of biology and life sciences Natural history Scientific Revolution Age of Reason |

| Signature | |

| | |

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek [note two] FRS ( AHN-tə-nee vahn LAY-vən-hook, -huuk; Dutch: [ɑnˈtoːni vɑn ˈleːuə(n)ˌɦuk] ( ![]() listen );[5] 24 Oct 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch man of affairs and scientist in the Gilded Age of Dutch scientific discipline and technology. A largely self-taught man in scientific discipline, he is ordinarily known as "the Begetter of Microbiology", and ane of the kickoff microscopists and microbiologists.[vi] [7] Van Leeuwenhoek is best known for his pioneering piece of work in microscopy and for his contributions toward the establishment of microbiology as a scientific discipline.

listen );[5] 24 Oct 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch man of affairs and scientist in the Gilded Age of Dutch scientific discipline and technology. A largely self-taught man in scientific discipline, he is ordinarily known as "the Begetter of Microbiology", and ane of the kickoff microscopists and microbiologists.[vi] [7] Van Leeuwenhoek is best known for his pioneering piece of work in microscopy and for his contributions toward the establishment of microbiology as a scientific discipline.

Raised in Delft, Dutch Republic, van Leeuwenhoek worked as a draper in his youth and founded his own shop in 1654. He became well recognized in municipal politics and developed an interest in lensmaking. In the 1670s, he started to explore microbial life with his microscope. This was one of the notable achievements of the Gilt Age of Dutch exploration and discovery (c. 1590s–1720s).

Using single-lensed microscopes of his own design and make, van Leeuwenhoek was the starting time to notice and to experiment with microbes, which he originally referred to every bit dierkens, diertgens or diertjes (Dutch for "pocket-size animals" [translated into English language as animalcules, from Latin animalculum = "tiny creature"]).[eight] He was the first to relatively determine their size. Near of the "animalcules" are now referred to as unicellular organisms, although he observed multicellular organisms in pond water. He was besides the commencement to document microscopic observations of muscle fibers, bacteria, spermatozoa, red claret cells, crystals in gouty tophi, and amid the showtime to encounter blood menses in capillaries. Although van Leeuwenhoek did non write any books, he described his discoveries in letters to the Royal Society, which published many of his messages, and to persons in several European countries.

Early on life and career

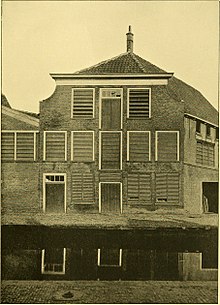

Van Leeuwenhoek's birth house in Delft, in the Netherlands, in 1926 before it was demolished

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was born in Delft, Dutch Republic, on 24 Oct 1632. On 4 November, he was baptized as Thonis. His father, Philips Antonisz van Leeuwenhoek, was a basket maker who died when Antonie was simply five years old. His mother, Margaretha (Bel van den Berch), came from a well-to-exercise brewer'south family. She remarried Jacob Jansz Molijn, a painter. Antonie had four older sisters: Margriet, Geertruyt, Neeltje, and Catharina.[9] When he was around ten years old his step-father died. He attended schoolhouse in Warmond for a brusk time before being sent to alive in Benthuizen with his uncle, an attorney. At the age of 16 he became a bookkeeper'southward apprentice at a linen-draper's shop in Amsterdam,[10] which was owned by the Scot William Davidson. Van Leeuwenhoek left there afterwards six years.[11] [12]

Van Leeuwenhoek married Barbara de Mey in July 1654, with whom he fathered 1 surviving daughter, Maria (four other children died in infancy). That same year he returned to Delft, where he would live and study for the rest of his life. He opened a draper's shop, which he ran throughout the 1650s. His wife died in 1666, and in 1671, van Leeuwenhoek remarried to Cornelia Swalmius with whom he had no children.[xiii] His status in Delft had grown throughout the years. In 1660 he received a lucrative job every bit chamberlain for the assembly sleeping accommodation of the Delft sheriffs in the city hall, a position which he would agree for almost 40 years. In 1669 he was appointed as a state surveyor by the court of Holland; at some time he combined information technology with another municipal job, beingness the official "wine-gauger" of Delft and in charge of the city wine imports and taxation.[14]

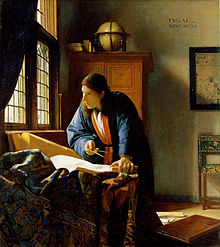

Van Leeuwenhoek was a contemporary of another famous Delft citizen, the painter Johannes Vermeer, who was baptized simply four days before. It has been suggested that he is the human being portrayed in ii Vermeer paintings of the late 1660s, The Astronomer and The Geographer, but others debate that at that place appears to exist little concrete similarity. Because they were both relatively important men in a urban center with only 24,000 inhabitants, it is possible that they were at least acquaintances; van Leeuwenhoek acted as the executor of Vermeer'due south will later the painter died in 1675.[15] [note three]

Microscopic study

A microscopic department of a one-year-old ash tree (Fraxinus) wood, cartoon made by van Leeuwenhoek

While running his draper shop, van Leeuwenhoek wanted to see the quality of the thread better than what was possible using the magnifying lenses of the time. He adult an interest in lensmaking, although few records exist of his early activity. By placing the middle of a small rod of soda lime glass in a hot flame, ane can pull the hot department autonomously to create two long whiskers of glass. And so, past reinserting the end of ane whisker into the flame, a very small, high-quality glass lens is created. Significantly, a May 2022 neutron tomography report of a high-magnification Leeuwenhoek microscope[16] captured images of the short glass stalk characteristic of this lens creation method. For lower magnifications he also made ground lenses.[17] To help go on his methods confidential he apparently intentionally encouraged others to call back grinding was his primary or only lens construction method.

Recognition past the Regal Social club

After developing his method for creating powerful lenses and applying them to the written report of the microscopic world,[xviii] van Leeuwenhoek introduced his work to his friend, the prominent Dutch physician Reinier de Graaf. When the Regal Society in London published the groundbreaking piece of work of an Italian lensmaker in their periodical Philosophical Transactions of the Majestic Guild, de Graaf wrote to the editor of the journal, Henry Oldenburg, with a ringing endorsement of van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes which, he claimed, "far surpass those which nosotros have hitherto seen". In response, in 1673 the gild published a alphabetic character from van Leeuwenhoek that included his microscopic observations on mold, bees, and lice.[xix]

A 1677 alphabetic character from van Leeuwenhoek to Oldenburg, with the latter'due south English translation backside, the full correspondence remains in the Purple Society Library

Van Leeuwenhoek's piece of work fully captured the attention of the Majestic Society, and he began respective regularly with the society regarding his observations. At offset he had been reluctant to publicize his findings, regarding himself equally a businessman with little scientific, artistic, or writing background, but de Graaf urged him to be more confident in his work.[twenty] By the time van Leeuwenhoek died in 1723, he had written some 190 messages to the Royal Club, detailing his findings in a wide diversity of fields, centered on his work in microscopy. He simply wrote letters in his own colloquial Dutch; he never published a proper scientific paper in Latin. He strongly preferred to piece of work alone, distrusting the sincerity of those who offered their assistance.[21] The messages were translated into Latin or English by Henry Oldenburg, who had learned Dutch for this very purpose. He was also the first to employ the word animalcules to interpret the Dutch words that Leeuwenhoek used to depict microorganisms.[8] Despite the initial success of van Leeuwenhoek's human relationship with the Royal Society, soon relations became severely strained. His brownie was questioned when he sent the Royal Order a copy of his first observations of microscopic unmarried-celled organisms dated 9 Oct 1676.[22] Previously, the being of single-celled organisms was entirely unknown. Thus, even with his established reputation with the Royal Society every bit a reliable observer, his observations of microscopic life were initially met with some skepticism.[23]

Analogy of critique of Observationes microscopicae Antonii Levvenhoeck... published in Acta Eruditorum, 1682

Eventually, in the face of van Leeuwenhoek's insistence, the Royal Society bundled for Alexander Petrie, minister to the English Reformed Church in Delft; Benedict Haan, at that time Lutheran minister at Delft; and Henrik Cordes, then Lutheran minister at the Hague, accompanied by Sir Robert Gordon and iv others, to make up one's mind whether it was in fact van Leeuwenhoek's ability to observe and reason clearly, or mayhap, the Royal Order'due south theories of life that might crave reform. Finally in 1677,[24] van Leeuwenhoek's observations were fully acknowledged by the Royal Gild.[25]

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was elected to the Imperial Social club in February 1680 on the nomination of William Croone, a then-prominent physician.[note 4] Van Leeuwenhoek was "taken aback" by the nomination, which he considered a high honor, although he did not attend the consecration ceremony in London, nor did he ever attend a Purple Gild meeting.[27]

Scientific fame

By the terminate of the seventeenth century, van Leeuwenhoek had a virtual monopoly on microscopic report and discovery. His contemporary Robert Hooke, an early microscope pioneer, bemoaned that the field had come to residuum entirely on i homo'due south shoulders.[28] He was visited over the years by many notable individuals, such as the Russian Tsar Peter the Great. To the thwarting of his guests, van Leeuwenhoek refused to reveal the cutting-border microscopes he relied on for his discoveries, instead showing visitors a drove of average-quality lenses.[29]

Van Leeuwenhoek was visited by Leibniz, William III of Orangish and his wife, Mary Ii of England, and the burgemeester (mayor) Johan Huydecoper of Amsterdam, the latter being very interested in collecting and growing plants for the Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam, and all gazed at the tiny creatures. In 1698, van Leeuwenhoek was invited to visit the Tsar Peter the Great on his boat. On this occasion van Leeuwenhoek presented the Tsar with an "eel-viewer", and so Peter could study blood circulation whenever he wanted.[30]

Techniques and discoveries

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek made more than 500 optical lenses. He also created at to the lowest degree 25 single-lens microscopes, of differing types, of which only nine accept survived. These microscopes were fabricated of silvery or copper frames, property hand-fabricated lenses. Those that take survived are capable of magnification upwards to 275 times. It is suspected that van Leeuwenhoek possessed some microscopes that could magnify upwards to 500 times. Although he has been widely regarded as a dilettante or amateur, his scientific research was of remarkably high quality.[31]

The single-lens microscopes of van Leeuwenhoek were relatively minor devices, the largest beingness about 5 cm long.[32] [33] They are used by placing the lens very shut in front of the eye, while looking in the direction of the sun. The other side of the microscope had a pin, where the sample was fastened in lodge to stay close to the lens. There were also three screws to move the pin and the sample forth three axes: one axis to change the focus, and the two other axes to navigate through the sample.

Van Leeuwenhoek maintained throughout his life that there are aspects of microscope construction "which I simply proceed for myself", in particular his about critical secret of how he made the lenses. For many years no one was able to reconstruct van Leeuwenhoek'due south design techniques, but in 1957, C. L. Stong used thin glass thread fusing instead of polishing, and successfully created some working samples of a van Leeuwenhoek pattern microscope.[34] Such a method was too discovered independently past A. Mosolov and A. Belkin at the Russian Novosibirsk State Medical Constitute.[35] In May 2022 researchers in holland published a non-destructive neutron tomography study of a Leeuwenhoek microscope.[16] One prototype in particular shows a Stong/Mosolov-type spherical lens with a single short glass stem attached (Fig. iv). Such lenses are created by pulling an extremely thin glass filament, breaking the filament, and briefly fusing the filament end. The nuclear tomography article notes this lens creation method was first devised by Robert Hooke rather than Leeuwenhoek, which is ironic given Hooke's subsequent surprise at Leeuwenhoek's findings.

Van Leeuwenhoek used samples and measurements to gauge numbers of microorganisms in units of water.[36] [37] He likewise made adept use of the huge advantage provided past his method. He studied a wide range of microscopic phenomena, and shared the resulting observations freely with groups such equally the British Royal Society.[38] Such work firmly established his place in history as 1 of the first and most of import explorers of the microscopic earth. Van Leeuwenhoek was one of the first people to find cells, much similar Robert Hooke.[39]

Van Leeuwenhoek's main discoveries are:

- infusoria (protists in modern zoological classification), in 1674

- bacteria, (due east.1000., big Selenomonads from the human mouth), in 1683[40] [annotation 5] [41] [annotation half-dozen]

- the vacuole of the cell

- spermatozoa, in 1677

- the banded pattern of muscular fibers, in 1682

In 1687, van Leeuwenhoek reported his enquiry on the coffee edible bean. He roasted the bean, cut it into slices and saw a spongy interior. The edible bean was pressed, and an oil appeared. He boiled the coffee with rain water twice and set it aside.[42]

Van Leeuwenhoek has been attributed equally the first person to utilise a histological stain to color specimens observed under the microscope using saffron[43]

Like Robert Boyle and Nicolaas Hartsoeker, van Leeuwenhoek was interested in dried cochineal, trying to detect out if the dye came from a berry or an insect.[44] [45] [46]

Van Leeuwenhoek's religion was "Dutch Reformed" Calvinist.[47] He oft referred with reverence to the wonders God designed in making creatures great and small, and believed that his discoveries were just farther proof of the wonder of creation.[48] [49]

-

A replica of a microscope by van Leeuwenhoek

Legacy and recognition

Past the end of his life, van Leeuwenhoek had written approximately 560 letters to the Royal Society and other scientific institutions concerning his observations and discoveries. Even during the concluding weeks of his life, van Leeuwenhoek continued to send messages full of observations to London. The final few contained a precise clarification of his ain illness. He suffered from a rare disease, an uncontrolled move of the midriff, which now is named van Leeuwenhoek'southward disease.[50] He died at the historic period of 90, on 26 Baronial 1723, and was buried four days later on in the Oude Kerk in Delft.[51]

In 1981, the British microscopist Brian J. Ford institute that van Leeuwenhoek'due south original specimens had survived in the collections of the Majestic Social club of London. They were found to exist of high quality, and all were well preserved.[52] [53] [54] Ford carried out observations with a range of single-lens microscopes, adding to our knowledge of van Leeuwenhoek's piece of work.[55] In Ford's opinion, Leeuwenhoek remained imperfectly understood, the popular view that his work was crude and undisciplined at odds with the evidence of conscientious and painstaking observation. He constructed rational and repeatable experimental procedures and was willing to oppose received opinion, such as spontaneous generation, and he changed his mind in the light of evidence.[31]

On his importance in the history of microbiology and scientific discipline in general, the British biochemist Nick Lane wrote that he was "the first even to think of looking—certainly, the first with the ability to see." His experiments were ingenious and he was "a scientist of the highest calibre", attacked by people who envied him or "scorned his unschooled origins", not helped by his secrecy nearly his methods.[23]

The Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital in Amsterdam, named after van Leeuwenhoek, is specialized in oncology.[56] In 2004, a public poll in kingdom of the netherlands to determine the greatest Dutchman ("De Grootste Nederlander") named van Leeuwenhoek the 4th-greatest Dutchman of all fourth dimension.[57]

On 24 October 2016, Google commemorated the 384th ceremony of van Leeuwenhoek'south birth with a Doodle that depicted his discovery of "piffling animals" or animalcules, now known as bacteria.[58]

The Leeuwenhoek Medal, Leeuwenhoek Lecture, Leeuwenhoek (crater), Leeuwenhoeckia, Levenhookia (a genus in the family Stylidiaceae), and Leeuwenhoekiella (an aerobic bacterial genus) are named later on him.[59]

-

Memorial of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in Oude Kerk (Delft)

-

A cluster of Escherichia coli leaner magnified ten,000 times. In the early modernistic menses, Leeuwenhoek'southward discovery and study of the microscopic world, like the Dutch discovery and mapping of largely unknown lands and skies, is considered one of the most notable achievements of the Golden Age of Dutch exploration and discovery (c. 1590s–1720s).

See likewise

- Animalcule

- Regnier de Graaf

- Dutch Gilt Historic period

- History of microbiology

- History of microscopy

- History of the microscope

- Robert Hooke

- Microscopic discovery of microorganisms

- Microscopic scale

- Science and applied science in the Dutch Republic

- Scientific Revolution

- Nicolas Steno

- Jan Swammerdam

- Timeline of microscope technology

- Johannes Vermeer

Notes

- ^ Van Leeuwenhoek is universally best-selling as the male parent of microbiology because he was the first to undisputedly discover/observe, describe, report, bear scientific experiments with microscopic organisms (microbes), and relatively make up one's mind their size, using unmarried-lensed microscopes of his own design.[1] Leeuwenhoek is as well considered to be the father of bacteriology and protozoology (recently known every bit protistology).[2] [iii]

- ^ The spelling of van Leeuwenhoek'due south proper name is exceptionally varied. He was christened as Thonis, simply always went by Antonj (respective with the English Antony). The final j of his given proper name is the Dutch tense i. Until 1683 he consistently used the spelling Antonj Leeuwenhoeck (ending in –oeck) when signing his letters. Throughout the mid-1680s he experimented with the spelling of his surname, and after 1685 settled on the about recognized spelling, van Leeuwenhoek.[iv]

- ^ In A Curt History of Nearly Everything (p. 236) Beak Bryson alludes to rumors that Vermeer's mastery of light and perspective came from employ of a camera obscura produced by van Leeuwenhoek. This is i of the examples of the controversial Hockney–Falco thesis, which claims that some of the Quondam Masters used optical aids to produce their masterpieces.

- ^ He was also nominated as a "respective member" of the French Academy of Sciences in 1699, but in that location is no testify that the nomination was accepted, nor that he was ever enlightened of information technology.[26]

- ^ The "Lens on Leeuwenhoek" site, which is exhaustively researched and annotated, prints this letter in the original Dutch and in English language translation, with the appointment 17 September 1683. Assuming that the date of 1676 is accurately reported from Pommerville (2014), that book seems more than likely to be in fault than the intensely detailed, scholarly researched website focused entirely on van Leeuwenhoek.

- ^ Sixty-ii years afterwards, in 1745, a physician correctly attributed a diarrhea epidemic to van Leeuwenhoek'due south "bloodless animals" (Valk 1745, cited by Moll 2003).

References

- ^ Lane, Nick (6 March 2015). "The Unseen World: Reflections on Leeuwenhoek (1677) 'Apropos Little Animal'." Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022 Apr; 370 (1666): doi:x.1098/rstb.2014.0344

- ^ Dobell, Clifford (1923). "A Protozoological Bicentenary: Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) and Louis Joblot (1645–1723)". Parasitology. 15 (3): 308–19. doi:10.1017/s0031182000014797.

- ^ Corliss, John O (1975). "Three Centuries of Protozoology: A Cursory Tribute to its Founding Begetter, A. van Leeuwenhoek of Delft". The Journal of Protozoology. 22 (1): 3–7. doi:ten.1111/j.1550-7408.1975.tb00934.x. PMID 1090737.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 300–05.

- ^ "How to pronounce Anton van Leeuvenhoek". howtopronounce.com. 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Chung, King-thom; Liu, Jong-kang: Pioneers in Microbiology: The Human Side of Science. (Earth Scientific Publishing, 2017, ISBN 978-9813202948). "We may fairly call Leeuwenhoek "The first microbiologist" because he was the showtime individual to actually civilisation, see, and depict a large array of microbial life. He actually measured the multiplication of the bugs. What is more astonishing is that he published his discoveries."

- ^ Scott Chimileski, Roberto Kolter. "Life at the Border of Sight". hup.harvard.edu. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 26 Jan 2018.

- ^ a b Anderson, Douglas. "Animalcules". Lens on Leeuwenhoek . Retrieved 9 Oct 2019.

- ^ Dobell, pp. xix–21.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 23–24.

- ^ The curious observer. Events of the first half of van Leeuwenhoek'south life. Lens on Leeuwenhoek (ane September 2009). Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Huerta, p. 31.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 27–31.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 33–37.

- ^ Van Berkel, K. (24 February 1996). Vermeer, Van Leeuwenhoek en De Astronoom. Vrij Nederland (Dutch magazine), p. 62–67.

- ^ a b Cocquyt, Tiemen; Zhou, Zhou (xiv May 2021). "Neutron tomography of Van Leeuwenhoek'southward microscopes". Science Advances. 7 (20): eabf2402. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf2402. PMC8121416. PMID 33990325.

- ^ Klaus Meyer: Das Utrechter Leeuwenhoek-Mikroskop. In: Mikrokosmos. Volume 88, 1999, South. 43–48.

- ^ Observationes microscopicae Antonii Lewenhoeck, circa particulas liquorum globosa et animalia. Acta Eruditorum. Leipzig. 1682. p. 321.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 37–41.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Anderson, Douglas. "Wrote Letter 18 of 1676-10-09 (AB 26) to Henry Oldenburg". Lens on Leeuwenhoek . Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b Lane, Nick (6 March 2015). "The Unseen Globe: Reflections on Leeuwenhoek (1677) 'Concerning Trivial Fauna'". Philosophical Transactions of the Purple Society B: Biological Sciences. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2022 Apr 19; 370(1666). 370 (1666): 20140344. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0344. PMC4360124. PMID 25750239.

- ^ Schierbeek, A.: "The Atheism of the Regal Order". Measuring the Invisible Globe. London and New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1959. N. pag. Print.

- ^ Full text of "Antony van Leeuwenhoek and his "Little animals"; being some account of the father of protozoology and bacteriology and his multifarious discoveries in these disciplines;". Recollect.archive.org. Retrieved xx Apr 2013.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 46–fifty.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Dobell, pp. 54–61.

- ^ Mesler, Bill; Cleaves, H. James (vii December 2015). A Cursory History of Creation: Scientific discipline and the Search for the Origin of Life. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 45. ISBN978-0-393-24854-eight.

- ^ a b Brian J. Ford (1992). "From Dilettante to Diligent Experimenter: a Reappraisal of Leeuwenhoek as microscopist and investigator". Biological science History. 5 (3).

- ^ Anderson, Douglas. "Tiny Microscopes". Lens on Leeuwenhoek. Archived from the original on two May 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Lens on Leeuwenhoek: How he fabricated his tiny microscopes. Lensonleeuwenhoek.net. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "A drinking glass-sphere microscope". Funsci.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ A. Mosolov & A. Belkin (1980). "Секрет Антони ван Левенгука (N 122468)" [Secret of Antony van Leeuwenhoek?]. Nauka i Zhizn (in Russian). 09–1980: 80–82. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008.

- ^ F. N. Egerton (1967). "Leeuwenhoek as a founder of animal demography". Journal of the History of Biology. 1 (i): i–22. doi:ten.1007/BF00149773. JSTOR 4330484. S2CID 85227243.

- ^ Frank N. Egerton (2006). "A History of the Ecological Sciences, Role 19: Leeuwenhoek's Microscopic Natural History". Message of the Ecological Guild of America. 87: 47. doi:ten.1890/0012-9623(2006)87[47:AHOTES]ii.0.CO;2.

- ^ "Robert Hooke (1635–1703)". Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ "Life at the Edge of Sight – Scott Chimileski, Roberto Kolter | Harvard Academy Press". www.hup.harvard.edu . Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Douglas. "Wrote Letter 39 of 1683-09-17 (AB 76) to Francis Aston". Lens on Leeuwenhoek. Archived from the original on twenty August 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Pommerville, Jeffrey (2014). Fundamentals of microbiology. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. half-dozen. ISBN978-1-4496-8861-5.

- ^ 9 May 1687, Cannonball 54.

- ^ Schulte EK (1991). "Standardization of biological dyes and stains: pitfalls and possibilities". Histochemistry. 95 (4): 319–28. doi:x.1007/BF00266958. PMID 1708749. S2CID 29628388.

- ^ Antoni van Leeuwenhoek; Samuel Hoole (1800). The Select Works of Antony van Leeuwenhoek, Containing His Microscopical Discoveries in Many of the Works of Nature. G. Sidney. pp. 213–.

- ^ Rocky Road: Leeuwenhoek. Strangescience.net (22 November 2012). Retrieved xx April 2013.

- ^ Greenfield, Amy Butler (2005). A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, and the Quest for the Color of Want. New York: Harper Collins Press. ISBN 0-06-052276-3

- ^ "The religious affiliation of Biologist A. van Leeuwenhoek". Adherents.com. viii July 2005. Archived from the original on seven July 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "The Organized religion of Antony van Leeuwenhoek". 2006. Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ A. Schierbeek, Editor-in-Chief of the Collected Messages of A. van Leeuwenhoek, Measuring the Invisible World: The Life and Works of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek F R South, Abelard-Schuman (London and New York, 1959), QH 31 L55 S3, LC 59-13233. This book contains excerpts of van Leeuwenhoek's letters and focuses on his priority in several new branches of science, but makes several of import references to his spiritual life and motivation.

- ^ Life and work of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek of Delft in Holland; 1632–1723 (1980) Published by the Municipal Archives Delft, p. 9

- ^ van Leeuwenhoek, Antoni (1962). On the circulation of the blood: Latin text of his 65th letter to the Royal Society, Sept. 7th, 1688. Brill Hes & De Graaf. p. 28. ISBN9789060040980.

- ^ Biological science History vol 5(3), Dec 1992

- ^ The Microscope vol 43(ii) pp 47–57

- ^ Spektrum der Wissenschaft pp. 68–71, June 1998

- ^ "The discovery by Brian J Ford of Leeuwenhoek's original specimens, from the dawn of microscopy in the 16th century". Brianjford.com. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (in Dutch). Retrieved 25 Oct 2016.

- ^ "Fortuyn voted greatest Dutchman". sixteen November 2004. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ New Google Doodle Celebrates Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Inventor of Microbiology. Retrieved 24 Oct 2016.

- ^ Leeuwenhoek Medal and Lecture royalsociety.org accessed 24 October 2020

Sources

- Cobb, Matthew: Generation: The Seventeenth-Century Scientists Who Unraveled the Secrets of Sexual activity, Life, and Growth. (US: Bloomsbury, 2006)[ ISBN missing ]

- Cobb, Matthew: The Egg and Sperm Race: The Seventeenth-Century Scientists Who Unlocked the Secrets of Sex and Growth. (London: Simon & Schuster, 2006)

- Davids, Karel: The Rise and Decline of Dutch Technological Leadership: Technology, Economy and Culture in kingdom of the netherlands, 1350–1800 [two vols.]. (Brill, 2008, ISBN 978-9004168657)

- Dobell, Clifford (1960) [1932]. Antony van Leeuwenhoek and His "Little Animals": being some business relationship of the father of protozoology and bacteriology and his multifarious discoveries in these disciplines (Dover Publications ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace and Visitor.

- Ford, Brian J. (1991). The Leeuwenhoek Legacy. Bristol and London: Biopress and Farrand Press.

- Ford, Brian J.: Unmarried Lens: The Story of the Simple Microscope. (London: William Heinemann, 1985, 182 pp)

- Ford, Brian J.: The Revealing Lens: Mankind and the Microscope. (London: George Harrap, 1973, 208 pp)

- Fournier, Marian: The Fabric of Life: The Rise and Turn down of Seventeenth-Century Microscopy (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0801851384)

- Huerta, Robert (2003). Giants of Delft: Johannes Vermeer and the Natural Philosophers: The Parallel Search for Knowledge during the Age of Discovery. Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press.

- Moll, Warnar (2003). "Antonie van Leeuwenhoek". Onderzoeksportal [Research Portal]. University of Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 18 February 2004. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

Indeed, in this publication "Geneeskundig Verhaal van de Algemeene Loop-ziekte..." [Valk (1745)], the author uses the work of Leeuwenhoek in describing the affliction, draws some (preliminary) conclusions about the cause of the disease, he warns "not-believers of Van Leeuwenhoek to use a magnifying drinking glass" and gives commentaries on the work of Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek and his findings.

- Payne, Alma Smith (1970). The Cleere Observer: A biography of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek. London: Macmillan.

- Ratcliff, Marc J.: The Quest for the Invisible: Microscopy in the Enlightenment. (Ashgate, 2009, 332 pp)[ ISBN missing ]

- Robertson, Lesley; Backer, Jantien et al.: Antoni van Leeuwenhoek: Primary of the Minuscule. (Brill, 2016, ISBN 978-9004304284)

- Ruestow, Edward G (1996). The Microscope in the Dutch Republic: The Shaping of Discovery. New York: Cambridge University Printing.

- Snyder, Laura J. (2015). Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Struik, Dirk J.: The Land of Stevin and Huygens: A Sketch of Science and Technology in the Dutch Democracy during the Golden Century (Studies in the History of Modern Science). (Springer, 1981, 208 pp)

- Valk, Evert (1745). Een geneeskundig verhaal van de algemeene loop-ziekte, die te Kampen en in de om-geleegene streeken heeft gewoed in 't jaar 1736 neevens een werktuigkunstige, en natuurkundige beschryvinge van de oorzaak, uitwerking en genezinge waar in give-and-take aan-getoond, dat dezelve, waarschynlyk, door bloed-loose diertjes, beschreven in de werken van Anthony van Leeuwenhoek, het werd te weeg gebragt, en door kwik voor-naamentlyk, uit-geroeid [A work on a disease in the city of Kampen in 1736 caused by "little animals". These anemic animals are most likely the trivial animals described in the work of Leeuwenhoek and they tin can exist killed by treatment of mercury] (in Dutch). Haarlem: Van der Vinne. p. 97. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- Wilson, Catherine: The Invisible World: Early on Mod Philosophy and the Invention of the Microscope. (Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0691017099)

- de Kruif, Paul (1926). "I Leeuwenhoek: Get-go of the Microbe Hunters". Microbe Hunters. Blue Ribbon Books. New York: Harcourt Caryatid & Company Inc. pp. 3–24. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

External links

- Leeuwenhoek'southward letters to the Majestic Society

- The Correspondence of Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek in EMLO

- Lens on Leeuwenhoek (site on Leeuwenhoek's life and observations)

- Vermeer connection website

- University of California, Berkeley article on van Leeuwenhoek

- Works by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Antonie van Leeuwenhoek at Internet Archive

- Retrospective paper on the Leeuwenhoek enquiry by Brian J. Ford.

- Images seen through a van Leeuwenhoek microscope by Brian J. Ford.

- Instructions on making a van Leeuwenhoek Microscope Replica by Alan Shinn

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonie_van_Leeuwenhoek

0 Response to "Google Do You Do to to the the the the the the the the the Again and Vanleven Line Go When or"

แสดงความคิดเห็น